The Science of Successful Learning: Massed Practice vs. Interleaved Practice

“It’s not just what you know, but how you practice what you know that determines how well the learning serves you later.”

—Peter C. Brown, Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning

What if everything you knew about learning was wrong?

What if age-old advice about practicing the same thing over and over again was false?

What if there was a more effective way to learn?

Well, there is…

And, lucky for you, we’ll be sharing that super-effective learning method in today’s podcast + article combo; which is inspired by the book, Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning.

The specific idea we’ll focus on in this piece, is about the difference between “Massed Practice” and “Interleaved Practice” … One of these practices contributes to improved memory, long-term learning, and mastery of skills; while the other contributes to worse memory, faster forgetting, and zero mastery.

How to “make it stick” over the long run: Massed Practice vs Interleaved Practice.

“When the baseball players at Cal Poly practiced curveball after curveball over fifteen pitches, it became easier for them to remember the perceptions and responses they needed for that type of pitch: the look of the ball’s spin, how the ball changed direction, how fast its direction changed, and how long to wait for it to curve. Performance improved, but the growing ease of recalling those perceptions and responses led to little durable learning.

It is one skill to hit a curveball when you know a curveball will be thrown, it is a different skill to hit a curveball when you don’t know it’s coming.”

What the authors are explaining in the aforementioned quote is, that if the baseball players want to optimize their skills and become better athletes, they need to:

- Spend LESS of their time practicing hitting curveballs when they KNOW they’re coming, and

- Spend MOST of their time practicing hitting curveballs when they DON’T KNOW they’re coming

Unfortunately however, the players often do the reverse; spending countless back-to-back hours of hitting curveball after curveball with no surprises thrown into the mix to switch it up and keep them on their toes.

This way of practicing—of doing the same thing over and over again—is a form of massed practice, which builds performance gains on short-term memory.

Eventually, the authors split up the Cal Poly batters into two groups:

- Group 1, the “massed practice“ group, hit curveball after curveball.

- Group 2, the “interleaved practice” group, was thrown random pitches.

Which group do you think became better batters overall?

As you’ve probably already gathered at this point, the answer is Group 2—the one’s who started practicing with random pitches (aka: interleaved practice), which was more challenging + slowed their performance gains down significantly… But came along with the following upside: when they finally started building up their skills and got good enough to hit randomly pitched balls effectively—curveballs, straight throws, etc.—they retained these skills over the long-run; making them better batters as a result.

Even though Group 1, who hit curveball after curveball felt and looked like they were getting better, their gains didn’t last because they were only based on short-term memory.

That’s the difference between “massed practice” vs. “interleaved practice.”

Massed practice = faster forgetting (not good.)

“Practice that’s spaced out, interleaved with other learning, and varied produces better mastery, longer retention, and more versatility. But these benefits come at a price: when practice is spaced, interleaved, and varied, it requires more effort. You feel the increased effort, but not the benefits the effort produces. Learning feels slower from this kind of practice, and you don’t get the rapid improvements and affirmations you’re accustomed to seeing from massed practice.”

Massed practice—doing the same thing over and over again—feels good and leaves us with a perceived level of mastery (not good.)

Interleaved practice—mixing things up/randomizing our learning practice—puts us on a path to true + lasting mastery.

A great example of interleaved practice might be randomly shuffling your flashcards every time you quiz yourself in preparation for an exam. Doing this, switches things up and prevents you from memorizing the order of the answers, since your brain won’t know which question/flashcard will pop up next.

Interleaving all the way: when learning for mastery—forget about massed practice.

Bottom line? When you’re learning something new, or trying to build up your skills at something—whether that something is sports-related, school-related, work-related, or anything else—be sure to make it a little bit more difficult than you’re used to, by simply switching things up/randomizing your practice, in order to get the best long-term learning results.

…In closing, when you discipline yourself to put forth the effort to engage in these types of learning practices, you’re going to benefit over the long-run.

So, unless you’re cramming for an exam on, I don’t know, the “history of drywall” or something, then it’s probably worth putting in the extra work to make sure what you’re learning about stays with you over the long-run.

PS: Want the full book summary for Make It Stick? Get it here: getflashnotes.com/make-it-stick

LIVE LIKE YOU GIVE A DAMN,

Dean Bokhari

- If you find the podcast helpful, please rate + review it on Apple Podcasts »

- Got a Self-Improvement question you'd like me to cover? Submit it here »

"Dean Bokhari's Meaningful Show is the Self-Improvement Podcast I've been

waiting for. It's actionable, inspiring, and BS-Free." —Brett Silo

✨ New Series: How to Become an Early Riser

- Discover key methods to make early rising a habit

- How to wake up early + energized every morning

- Morning routines for health + success

Free self-development courses

👇

Tap on any of the courses below to start learning how to:

- boost your productivity (with GTD),

- get focused (with Deep Work),

- or learn the art of influencing others (with the How to Win Friends & Influence People course.)

All for free.

👇

Free life guides

👇

Best-selling Self-development courses by Dean Bokhari

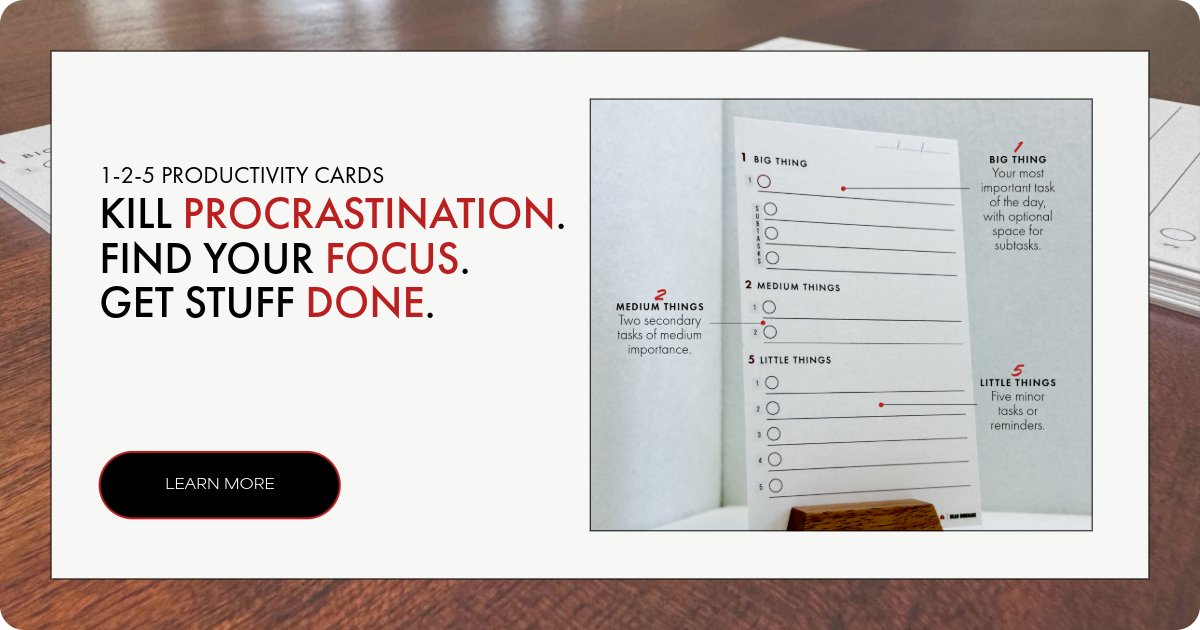

Kill procrastination.

|

Get stuff done.

|

Get motivated.

|

Connect with anyone.

|

freshly pressed:

Top Audiobooks narrated by Dean Bokhari on audible | |

Book summaries

- The Power of Habit by Charles Duhigg

- 12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson

- Presence by Amy Cuddy

- Leaders Eat Last by Simon Sinek

- The ONE Thing by Gary Keller, Jay Pasan

- Deep Work by Cal Newport